This is

HistoPedia Beta2.0, await the finishing touch.

Select the timeline below

Euclid of Alexandria

Euclid of Alexandria

Life

Of Euclid’s life nothing is known except what the Greek philosopher

Proclus (c. 410–485 CE) reports in his “summary” of famous Greek

mathematicians. According to him, Euclid taught at Alexandria in the

time of Ptolemy I Soter, who reigned over Egypt from 323 to 285 BCE.

Medieval translators and editors often confused him with the

philosopher Eukleides of Megara, a contemporary of Plato about a

century before, and therefore called him Megarensis. Proclus

supported his date for Euclid by writing “Ptolemy once asked Euclid

if there was not a shorter road to geometry than through the

Elements, and Euclid replied that there was no royal road to

geometry.” Today few historians challenge the consensus that Euclid

was older than Archimedes (c. 290–212/211 BCE).

Pending...

Pending...

Hypsicles of Alexandria

Hypsicles of Alexandria

Summary

Hypsicles was a Greek mathematician who wrote a treatise on regular

polyhedra. He is the author of what has been called Book XIV of

Euclid's Elements, a work which deals with inscribing regular solids

in a sphere.

Hypsicles of Alexandria wrote a treatise on regular polyhedra. He is the author of what has been called Book XIV of Euclid's Elements, a work which deals with inscribing regular solids in a sphere. What little is known of Hypsicles' life is related by him in the preface to the so-called Book XIV. He writes that Basilides of Tyre came to Alexandria and there he discussed mathematics with Hypsicles' father. Hypsicles relates that his father and Basilides studied a treatise by Apollonius on a dodecahedron and an icosahedron in the same sphere and decided that Apollonius's treatment was not satisfactory. In the so-called Book XIV Hypsicles proves some results due to Apollonius. He had clearly studied Apollonius's tract on inscribing a dodecahedron and an icosahedron in the same sphere and clearly had, as his father and Basilides before him, found it poorly presented and Hypsicles attempts to improve on Apollonius's treatment. Arab writers also claim that Hypsicles was involved with the so-called Book XV of the Elements. Bulmer-Thomas writes in [1] that various aspects are ascribed to him, claiming that either:- ... he wrote it, edited it, or merely discovered it. But this is clearly a much later and much inferior book, in three separate parts, and this speculation appears to derive from a misunderstanding of the preface to Book XIV.

Pending...

Hypsicles of Alexandria wrote a treatise on regular polyhedra. He is the author of what has been called Book XIV of Euclid's Elements, a work which deals with inscribing regular solids in a sphere. What little is known of Hypsicles' life is related by him in the preface to the so-called Book XIV. He writes that Basilides of Tyre came to Alexandria and there he discussed mathematics with Hypsicles' father. Hypsicles relates that his father and Basilides studied a treatise by Apollonius on a dodecahedron and an icosahedron in the same sphere and decided that Apollonius's treatment was not satisfactory. In the so-called Book XIV Hypsicles proves some results due to Apollonius. He had clearly studied Apollonius's tract on inscribing a dodecahedron and an icosahedron in the same sphere and clearly had, as his father and Basilides before him, found it poorly presented and Hypsicles attempts to improve on Apollonius's treatment. Arab writers also claim that Hypsicles was involved with the so-called Book XV of the Elements. Bulmer-Thomas writes in [1] that various aspects are ascribed to him, claiming that either:- ... he wrote it, edited it, or merely discovered it. But this is clearly a much later and much inferior book, in three separate parts, and this speculation appears to derive from a misunderstanding of the preface to Book XIV.

Pending...

Ahmes

Ahmes

Summary :

Ahmes was the Egyptian scribe who wrote the Rhind Papyrus - one of the oldest known mathematical documents.

Ahmes is the scribe who wrote the Rhind Papyrus (named after the Scottish Egyptologist Alexander Henry Rhind who went to Thebes for health reasons, became interested in excavating and purchased the papyrus in Egypt in 1858). Ahmes claims not to be the author of the work, being, he claims, only a scribe. He says that the material comes from an earlier work of about 2000 BC. The papyrus is our chief source of information on Egyptian mathematics. The Recto contains division of 2 by the odd numbers 3 to 101 in unit fractions and the numbers 1 to 9 by 10. The Verso has 87 problems on the four operations, solution of equations, progressions, volumes of granaries, the two-thirds rule etc. The Rhind Papyrus, which came to the British Museum in 1863, is sometimes called the 'Ahmes papyrus' in honour of Ahmes. Nothing is known of Ahmes other than his own comments in the papyrus.

The Rhind papyrus

Pending...

Ahmes was the Egyptian scribe who wrote the Rhind Papyrus - one of the oldest known mathematical documents.

Ahmes is the scribe who wrote the Rhind Papyrus (named after the Scottish Egyptologist Alexander Henry Rhind who went to Thebes for health reasons, became interested in excavating and purchased the papyrus in Egypt in 1858). Ahmes claims not to be the author of the work, being, he claims, only a scribe. He says that the material comes from an earlier work of about 2000 BC. The papyrus is our chief source of information on Egyptian mathematics. The Recto contains division of 2 by the odd numbers 3 to 101 in unit fractions and the numbers 1 to 9 by 10. The Verso has 87 problems on the four operations, solution of equations, progressions, volumes of granaries, the two-thirds rule etc. The Rhind Papyrus, which came to the British Museum in 1863, is sometimes called the 'Ahmes papyrus' in honour of Ahmes. Nothing is known of Ahmes other than his own comments in the papyrus.

The Rhind papyrus

Pending...

Archimedes of Syracuse

Archimedes of Syracuse

...

al-Khwārizmī

al-Khwārizmī

...

Maria Gaëtana Agnesi

Maria Gaëtana Agnesi

Summary :

Maria Agnesi was an Italian mathematician who is noted for her work in differential calculus. She discussed the cubic curve now known as the 'witch of Agnesi'.

She was the daughter of Pietro Agnesi who came from a wealthy family who had made their money from silk. Pietro Agnesi had twenty-one children with his three wives and Maria was the eldest of the children. As Truesdell writes in [20], Pietro Agnesi:-

Some accounts of Maria Agnesi describe her father as being a professor of mathematics at Bologna. It is shown clearly in [16] that this is entirely incorrect, but the error is unfortunately carried forward to [1] and will also be seen in a number of other places. Pietro Agnesi could provide high quality tutors for Maria Agnesi and indeed he did provide her with the best available tutors who were all young men of learning from the Church. She showed remarkable talents and mastered many languages such as Latin, Greek and Hebrew at an early age. At the age of 9 she published a Latin discourse in defence of higher education for women. It was not Agnesi's composition, as has been claimed by some, but rather it was an article written in Italian by one of her tutors which she translated and [20]:-

Pending......

Maria Agnesi was an Italian mathematician who is noted for her work in differential calculus. She discussed the cubic curve now known as the 'witch of Agnesi'.

She was the daughter of Pietro Agnesi who came from a wealthy family who had made their money from silk. Pietro Agnesi had twenty-one children with his three wives and Maria was the eldest of the children. As Truesdell writes in [20], Pietro Agnesi:-

Some accounts of Maria Agnesi describe her father as being a professor of mathematics at Bologna. It is shown clearly in [16] that this is entirely incorrect, but the error is unfortunately carried forward to [1] and will also be seen in a number of other places. Pietro Agnesi could provide high quality tutors for Maria Agnesi and indeed he did provide her with the best available tutors who were all young men of learning from the Church. She showed remarkable talents and mastered many languages such as Latin, Greek and Hebrew at an early age. At the age of 9 she published a Latin discourse in defence of higher education for women. It was not Agnesi's composition, as has been claimed by some, but rather it was an article written in Italian by one of her tutors which she translated and [20]:-

Pending......

Giovanni Battista Benedetti

Giovanni Battista Benedetti

.....

Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla

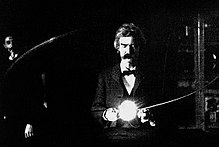

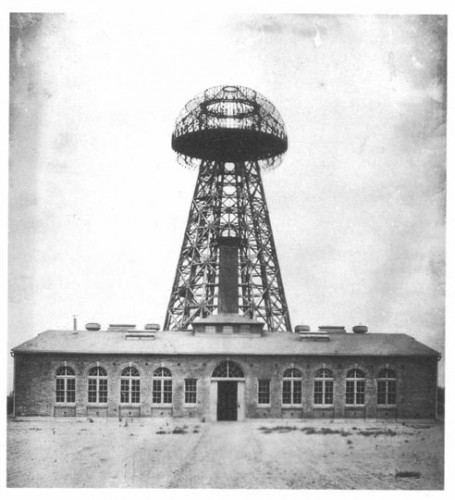

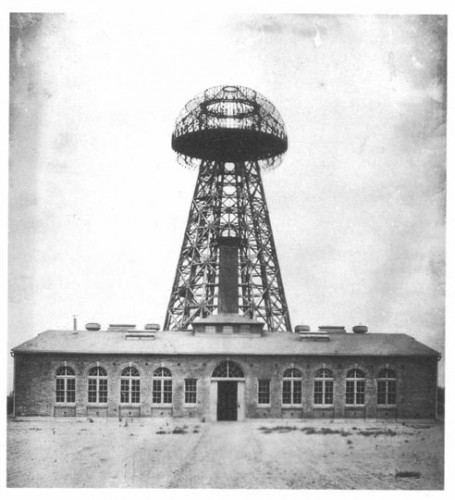

The inventor’s vision of a global wireless-transmission tower

proved to be his undoing

Tesla believed his mind to be without equal, and he wasn’t above chiding his contemporaries, such as Thomas Edison, who once hired him. “If Edison had a needle to find in a haystack,” Tesla once wrote, “he would proceed at once with the diligence of the bee to examine straw after straw until he found the object of his search. I was a sorry witness of such doing that a little theory and calculation would have saved him ninety percent of his labor.” But what his contemporaries may have been lacking in scientific talent (by Tesla’s estimation), men like Edison and George Westinghouse clearly possessed the one trait that Tesla did not—a mind for business. And in the last days of America’s Gilded Age, Nikola Tesla made a dramatic attempt to change the future of communications and power transmission around the world. He managed to convince J.P. Morgan that he was on the verge of a breakthrough, and the financier gave Tesla more than $150,000 to fund what would become a gigantic, futuristic and startling tower in the middle of Long Island, New York. In 1898, as Tesla’s plans to create a worldwide wireless transmission system became known, Wardenclyffe Tower would be Tesla’s last chance to claim the recognition and wealth that had always escaped him. Nikola Tesla was born in modern-day Croatia in 1856; his father, Milutin, was a priest of the Serbian Orthodox Church. From an early age, he demonstrated the obsessiveness that would puzzle and amuse those around him. He could memorize entire books and store logarithmic tables in his brain. He picked up languages easily, and he could work through days and nights on only a few hours sleep. At the age of 19, he was studying electrical engineering at the Polytechnic Institute at Graz in Austria, where he quickly established himself as a star student. He found himself in an ongoing debate with a professor over perceived design flaws in the direct-current (DC) motors that were being demonstrated in class. “In attacking the problem again I almost regretted that the struggle was soon to end,” Tesla later wrote. “I had so much energy to spare. When I undertook the task it was not with a resolve such as men often make. With me it was a sacred vow, a question of life and death. I knew that I would perish if I failed. Now I felt that the battle was won. Back in the deep recesses of the brain was the solution, but I could not yet give it outward expression.”

He would spend the next six years of his life “thinking” about electromagnetic fields and a hypothetical motor powered by alternate-current that would and should work. The thoughts obsessed him, and he was unable to focus on his schoolwork. Professors at the university warned Tesla’s father that the young scholar’s working and sleeping habits were killing him. But rather than finish his studies, Tesla became a gambling addict, lost all his tuition money, dropped out of school and suffered a nervous breakdown. It would not be his last. In 1881, Tesla moved to Budapest, after recovering from his breakdown, and he was walking through a park with a friend, reciting poetry, when a vision came to him. There in the park, with a stick, Tesla drew a crude diagram in the dirt—a motor using the principle of rotating magnetic fields created by two or more alternating currents. While AC electrification had been employed before, there would never be a practical, working motor run on alternating current until he invented his induction motor several years later. In June 1884, Tesla sailed for New York City and arrived with four cents in his pocket and a letter of recommendation from Charles Batchelor—a former employer—to Thomas Edison, which was purported to say, “My Dear Edison: I know two great men and you are one of them. The other is this young man!” A meeting was arranged, and once Tesla described the engineering work he was doing, Edison, though skeptical, hired him. According to Tesla, Edison offered him $50,000 if he could improve upon the DC generation plants Edison favored. Within a few months, Tesla informed the American inventor that he had indeed improved upon Edison’s motors. Edison, Tesla noted, refused to pay up. “When you become a full-fledged American, you will appreciate an American joke,” Edison told him. Tesla promptly quit and took a job digging ditches. But it wasn’t long before word got out that Tesla’s AC motor was worth investing in, and the Western Union Company put Tesla to work in a lab not far from Edison’s office, where he designed AC power systems that are still used around the world. “The motors I built there,” Tesla said, “were exactly as I imagined them. I made no attempt to improve the design, but merely reproduced the pictures as they appeared to my vision, and the operation was always as I expected.”

Tesla patented his AC motors and power systems, which were said to be the most valuable inventions since the telephone. Soon, George Westinghouse, recognizing that Tesla’s designs might be just what he needed in his efforts to unseat Edison’s DC current, licensed his patents for $60,000 in stocks and cash and royalties based on how much electricity Westinghouse could sell. Ultimately, he won the “War of the Currents,” but at a steep cost in litigation and competition for both Westinghouse and Edison’s General Electric Company.

Fearing ruin, Westinghouse begged Tesla for relief from the royalties Westinghouse agreed to. “Your decision determines the fate of the Westinghouse Company,” he said. Tesla, grateful to the man who had never tried to swindle him, tore up the royalty contract, walking away from millions in royalties that he was already owed and billions that would have accrued in the future. He would have been one of the wealthiest men in the world—a titan of the Gilded Age. His work with electricity reflected just one facet of his fertile mind. Before the turn of the 20th century, Tesla had invented a powerful coil that was capable of generating high voltages and frequencies, leading to new forms of light, such as neon and fluorescent, as well as X-rays. Tesla also discovered that these coils, soon to be called “Tesla Coils,” made it possible to send and receive radio signals. He quickly filed for American patents in 1897, beating the Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi to the punch. Tesla continued to work on his ideas for wireless transmissions when he proposed to J.P. Morgan his idea of a wireless globe. After Morgan put up the $150,000 to build the giant transmission tower, Tesla promptly hired the noted architect Stanford White of McKim, Mead, and White in New York. White, too, was smitten with Tesla’s idea. After all, Tesla was the highly acclaimed man behind Westinghouse’s success with alternating current, and when Tesla talked, he was persuasive.

“As soon as completed, it will be possible for a business man in New York to dictate instructions, and have them instantly appear in type at his office in London or elsewhere,” Tesla said at the time. “He will be able to call up, from his desk, and talk to any telephone subscriber on the globe, without any change whatever in the existing equipment. An inexpensive instrument, not bigger than a watch, will enable its bearer to hear anywhere, on sea or land, music or song, the speech of a political leader, the address of an eminent man of science, or the sermon of an eloquent clergyman, delivered in some other place, however distant. In the same manner any picture, character, drawing or print can be transferred from one to another place. Millions of such instruments can be operated from but one plant of this kind.” White quickly got to work designing Wardenclyffe Tower in 1901, but soon after construction began it became apparent that Tesla was going to run out of money before it was finished. An appeal to Morgan for more money proved fruitless, and in the meantime investors were rushing to throw their money behind Marconi. In December 1901, Marconi successfully sent a signal from England to Newfoundland. Tesla grumbled that the Italian was using 17 of his patents, but litigation eventually favored Marconi and the commercial damage was done. (The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately upheld Tesla’s claims, clarifying Tesla’s role in the invention of the radio—but not until 1943, after he died.) Thus the Italian inventor was credited as the inventor of radio and became rich. Wardenclyffe Tower became a 186-foot-tall relic (it would be razed in 1917), and the defeat—Tesla’s worst—led to another of his breakdowns. ”It is not a dream,” Tesla said, “it is a simple feat of scientific electrical engineering, only expensive—blind, faint-hearted, doubting world!”

By 1912, Tesla began to withdraw from that doubting world. He was clearly showing signs of obsessive-compulsive disorder, and was potentially a high-functioning autistic. He became obsessed with cleanliness and fixated on the number three; he began shaking hands with people and washing his hands—all done in sets of three. He had to have 18 napkins on his table during meals, and would count his steps whenever he walked anywhere. He claimed to have an abnormal sensitivity to sounds, as well as an acute sense of sight, and he later wrote that he had “a violent aversion against the earrings of women,” and “the sight of a pearl would almost give me a fit.” Near the end of his life, Tesla became fixated on pigeons, especially a specific white female, which he claimed to love almost as one would love a human being. One night, Tesla claimed the white pigeon visited him through an open window at his hotel, and he believed the bird had come to tell him she was dying. He saw “two powerful beans of light” in the bird’s eyes, he later said. “Yes, it was a real light, a powerful, dazzling, blinding light, a light more intense than I had ever produced by the most powerful lamps in my laboratory.” The pigeon died in his arms, and the inventor claimed that in that moment, he knew that he had finished his life’s work.

Tesla believed his mind to be without equal, and he wasn’t above chiding his contemporaries, such as Thomas Edison, who once hired him. “If Edison had a needle to find in a haystack,” Tesla once wrote, “he would proceed at once with the diligence of the bee to examine straw after straw until he found the object of his search. I was a sorry witness of such doing that a little theory and calculation would have saved him ninety percent of his labor.” But what his contemporaries may have been lacking in scientific talent (by Tesla’s estimation), men like Edison and George Westinghouse clearly possessed the one trait that Tesla did not—a mind for business. And in the last days of America’s Gilded Age, Nikola Tesla made a dramatic attempt to change the future of communications and power transmission around the world. He managed to convince J.P. Morgan that he was on the verge of a breakthrough, and the financier gave Tesla more than $150,000 to fund what would become a gigantic, futuristic and startling tower in the middle of Long Island, New York. In 1898, as Tesla’s plans to create a worldwide wireless transmission system became known, Wardenclyffe Tower would be Tesla’s last chance to claim the recognition and wealth that had always escaped him. Nikola Tesla was born in modern-day Croatia in 1856; his father, Milutin, was a priest of the Serbian Orthodox Church. From an early age, he demonstrated the obsessiveness that would puzzle and amuse those around him. He could memorize entire books and store logarithmic tables in his brain. He picked up languages easily, and he could work through days and nights on only a few hours sleep. At the age of 19, he was studying electrical engineering at the Polytechnic Institute at Graz in Austria, where he quickly established himself as a star student. He found himself in an ongoing debate with a professor over perceived design flaws in the direct-current (DC) motors that were being demonstrated in class. “In attacking the problem again I almost regretted that the struggle was soon to end,” Tesla later wrote. “I had so much energy to spare. When I undertook the task it was not with a resolve such as men often make. With me it was a sacred vow, a question of life and death. I knew that I would perish if I failed. Now I felt that the battle was won. Back in the deep recesses of the brain was the solution, but I could not yet give it outward expression.”

He would spend the next six years of his life “thinking” about electromagnetic fields and a hypothetical motor powered by alternate-current that would and should work. The thoughts obsessed him, and he was unable to focus on his schoolwork. Professors at the university warned Tesla’s father that the young scholar’s working and sleeping habits were killing him. But rather than finish his studies, Tesla became a gambling addict, lost all his tuition money, dropped out of school and suffered a nervous breakdown. It would not be his last. In 1881, Tesla moved to Budapest, after recovering from his breakdown, and he was walking through a park with a friend, reciting poetry, when a vision came to him. There in the park, with a stick, Tesla drew a crude diagram in the dirt—a motor using the principle of rotating magnetic fields created by two or more alternating currents. While AC electrification had been employed before, there would never be a practical, working motor run on alternating current until he invented his induction motor several years later. In June 1884, Tesla sailed for New York City and arrived with four cents in his pocket and a letter of recommendation from Charles Batchelor—a former employer—to Thomas Edison, which was purported to say, “My Dear Edison: I know two great men and you are one of them. The other is this young man!” A meeting was arranged, and once Tesla described the engineering work he was doing, Edison, though skeptical, hired him. According to Tesla, Edison offered him $50,000 if he could improve upon the DC generation plants Edison favored. Within a few months, Tesla informed the American inventor that he had indeed improved upon Edison’s motors. Edison, Tesla noted, refused to pay up. “When you become a full-fledged American, you will appreciate an American joke,” Edison told him. Tesla promptly quit and took a job digging ditches. But it wasn’t long before word got out that Tesla’s AC motor was worth investing in, and the Western Union Company put Tesla to work in a lab not far from Edison’s office, where he designed AC power systems that are still used around the world. “The motors I built there,” Tesla said, “were exactly as I imagined them. I made no attempt to improve the design, but merely reproduced the pictures as they appeared to my vision, and the operation was always as I expected.”

Tesla patented his AC motors and power systems, which were said to be the most valuable inventions since the telephone. Soon, George Westinghouse, recognizing that Tesla’s designs might be just what he needed in his efforts to unseat Edison’s DC current, licensed his patents for $60,000 in stocks and cash and royalties based on how much electricity Westinghouse could sell. Ultimately, he won the “War of the Currents,” but at a steep cost in litigation and competition for both Westinghouse and Edison’s General Electric Company.

Fearing ruin, Westinghouse begged Tesla for relief from the royalties Westinghouse agreed to. “Your decision determines the fate of the Westinghouse Company,” he said. Tesla, grateful to the man who had never tried to swindle him, tore up the royalty contract, walking away from millions in royalties that he was already owed and billions that would have accrued in the future. He would have been one of the wealthiest men in the world—a titan of the Gilded Age. His work with electricity reflected just one facet of his fertile mind. Before the turn of the 20th century, Tesla had invented a powerful coil that was capable of generating high voltages and frequencies, leading to new forms of light, such as neon and fluorescent, as well as X-rays. Tesla also discovered that these coils, soon to be called “Tesla Coils,” made it possible to send and receive radio signals. He quickly filed for American patents in 1897, beating the Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi to the punch. Tesla continued to work on his ideas for wireless transmissions when he proposed to J.P. Morgan his idea of a wireless globe. After Morgan put up the $150,000 to build the giant transmission tower, Tesla promptly hired the noted architect Stanford White of McKim, Mead, and White in New York. White, too, was smitten with Tesla’s idea. After all, Tesla was the highly acclaimed man behind Westinghouse’s success with alternating current, and when Tesla talked, he was persuasive.

“As soon as completed, it will be possible for a business man in New York to dictate instructions, and have them instantly appear in type at his office in London or elsewhere,” Tesla said at the time. “He will be able to call up, from his desk, and talk to any telephone subscriber on the globe, without any change whatever in the existing equipment. An inexpensive instrument, not bigger than a watch, will enable its bearer to hear anywhere, on sea or land, music or song, the speech of a political leader, the address of an eminent man of science, or the sermon of an eloquent clergyman, delivered in some other place, however distant. In the same manner any picture, character, drawing or print can be transferred from one to another place. Millions of such instruments can be operated from but one plant of this kind.” White quickly got to work designing Wardenclyffe Tower in 1901, but soon after construction began it became apparent that Tesla was going to run out of money before it was finished. An appeal to Morgan for more money proved fruitless, and in the meantime investors were rushing to throw their money behind Marconi. In December 1901, Marconi successfully sent a signal from England to Newfoundland. Tesla grumbled that the Italian was using 17 of his patents, but litigation eventually favored Marconi and the commercial damage was done. (The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately upheld Tesla’s claims, clarifying Tesla’s role in the invention of the radio—but not until 1943, after he died.) Thus the Italian inventor was credited as the inventor of radio and became rich. Wardenclyffe Tower became a 186-foot-tall relic (it would be razed in 1917), and the defeat—Tesla’s worst—led to another of his breakdowns. ”It is not a dream,” Tesla said, “it is a simple feat of scientific electrical engineering, only expensive—blind, faint-hearted, doubting world!”

By 1912, Tesla began to withdraw from that doubting world. He was clearly showing signs of obsessive-compulsive disorder, and was potentially a high-functioning autistic. He became obsessed with cleanliness and fixated on the number three; he began shaking hands with people and washing his hands—all done in sets of three. He had to have 18 napkins on his table during meals, and would count his steps whenever he walked anywhere. He claimed to have an abnormal sensitivity to sounds, as well as an acute sense of sight, and he later wrote that he had “a violent aversion against the earrings of women,” and “the sight of a pearl would almost give me a fit.” Near the end of his life, Tesla became fixated on pigeons, especially a specific white female, which he claimed to love almost as one would love a human being. One night, Tesla claimed the white pigeon visited him through an open window at his hotel, and he believed the bird had come to tell him she was dying. He saw “two powerful beans of light” in the bird’s eyes, he later said. “Yes, it was a real light, a powerful, dazzling, blinding light, a light more intense than I had ever produced by the most powerful lamps in my laboratory.” The pigeon died in his arms, and the inventor claimed that in that moment, he knew that he had finished his life’s work.

Tomás Rodríguez Bachiller

Tomás Rodríguez Bachiller

He was born in Hong Kong. His father, Tomás Rodríguez y Rodríguez de

Medio, had been born in Cobreros, Zamore, and had trained as a

lawyer before having a career as a consul. At the time when his son

was born, he was the Spanish Vice-Consul in what was, at that time,

the British colony of Hong Kong. His second wife was Julia Bachiller

Fernández Ruiz, from Montemayor de Pililla, in Valladolid, who

became a full-time housewife looking after the family. There were

five children in the family, the two oldest being the girls Julia

and Pilar, both children of Tomás Rodríguez's first marriage, and

three boys from the second marriage, Tomás (the subject of this

biography), Ángel and Jesús. Ángel was born in Montemayor and Jesús

was born in Puerto Rico, where Tomás Rodríguez was serving as consul

at the time. Their mother, Julia, died as a result of childbirth

when Jesús was born and was buried in Puerto Rico. Tomás Bachiller

and his two brothers began their first studies in Ayamonte, Huelva,

Spain, and studied there until the family settled in Madrid. From

that time the three brothers were put in charge of the older sisters

while their father continued his consular career, making frequent

and long stays abroad.

At the age of fourteen Bachiller went to Central University of

Madrid to attend mathematics lectures by José Echegaray. At this

time he was studying at the Cardinal Cisneros Institute in Madrid, a

leading high school in Madrid. There he showed himself to be an

exceptionally talented student, and he graduated on 16 June 1916.

Following graduation, Bachiller enrolled as a student at the Central

University of Madrid to study mathematics. His father, however,

believed that his son would never be able to make a good career for

himself as a mathematician so, in 1918, he enrolled as a student in

the Madrid School of Civil Engineering and began studying there in

parallel to his studies in mathematics at the Central University. He

attended courses on mathematical analysis given by Luis Octavio de

Toledo (1857-1934), Julio Rey Pastor (who was in Argentina much of

1917-18 ), and José Ruiz Castizo (1857-1929), who was also taught a

course on rational mechanics. Bachiller studied geometry with

Cecilio Jiménez Rueda (1858-1950), Miguel Vegas (1856-1943),

Faustino Archilla (1870-1939) and José G Álvarez Ude (1876-1958).

In January 1921, Tullio Levi-Civita made a visit to Madrid and gave

a course on "Classical and relativistic mechanics". Bachiller

translated the lectures into Spanish and wrote them up for

publication, but despite his efforts, the notes were never

published. In 1921-22 Bachiller studied "Celestial Mechanics" given

by José María Plans (1878-1934). In 1923 Einstein visited Spain and

before the visit the Mathematical Society held two sessions at 8

Santa Teresa Street to prepare for Einstein's lectures. On 7 March

1923 Einstein lectured to the Mathematical Society and, after a

question by Bachiller, discussed the matter with him for half and

hour. When Einstein gave a series of three public lectures on

relativity on 5, 6 and 8 March, Bachiller was told to attend them,

take notes and prepare summaries. When Bachiller's abstracts of the

lectures were published, Bachiller provided copies to Einstein who

told him that "in no other country in the world had they done so

well".

In May 1923 Bachiller applied to the Junta para la Ampliación de

Estudios (now the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas)

for a one-year scholarship in order to study the theory of functions

and differential equations in Germany and Switzerland. He stated

that he had knowledge of French, English, German and Italian. We

learn from this application that at this stage Bachiller intended to

write a doctoral thesis on the algebraic geometry of the style

studied by Francesco Severi's school in Italy. This scholarship was

not awarded but the Faculty of Sciences in Madrid awarded Bachiller

a scholarship to enable him to spend the academic year 1923-24

studying in France. He arrived in Paris in November 1923 and

attended courses at the Collège de France and at the Sorbonne. In

particular he attended Émile Borel's course on elasticity, Jules

Drach's course on contact transformations, Émile Picard's course on

algebraic curves and surfaces, Élie Cartan's course on fluid

mechanics, Jacques Hadamard's course on differential equations, the

course that Claude Guichard (1861-1924) delivered on differential

geometry and Laplace transformations, Henri Lebesgue's course on

topology and Ernest Vessiot's courses on partial differential

equations and on group theory. When Bachiller returned to Madrid in

1924 he delivered the first topology course ever given in Spain.

Back at the Faculty of Sciences in Madrid, Bachiller was appointed

as an assistant on 2 October 1925 to give practical classes on

"Elements of Infinitesimal Calculus", and on 13 November of that

year also on "Spherical Astronomy and Geodesy". He was very active

in working for the Journal of the Spanish Mathematical Society. He

reviewed work of mathematicians across the whole of Europe, in

particular writings articles on the topology of Maurice Fréchet, the

doctoral theses of Luigi Fantappié on algebraic geometry and of

Louis Antoine on topology, and the monograph L'Analysis situs et la

Géométrie algébrique Ⓣ written by Solomon Lefschetz for the Borel

Collection. Another of his tasks was to keep up a correspondence

with foreign mathematicians who published in the first issues of the

Journal, such as Hermann Weyl, Tullio Levi-Civita, Albert Einstein

and Edmund Landau, as well as translating some of their articles

into Spanish. Among the articles he wrote at this time we mention:

El professor F Klein Ⓣ (1925); Answering Problem 24 (as set out in

Revista Mat., Hisp.-Amerika 2 (1920), 278) (Spanish); La

correspondencia biunívoca de Cantor y el teorema de Netto Ⓣ (1926);

Conjuntos cerrados no densos Ⓣ (1926); Conferencias del Prof Dr

Terradas Ⓣ (1927); and Sobre el numero de dimensiones de un conjunto

Ⓣ (1927).

On 6 May 1926 Bachiller married Pilar Pradilla with his friend

Fernando Lorente de No as a witness. Pilar was 21 years old and from

Torreblanca, Castellón de la Plana. Tomás and Pilar Bachiller had

three children: Tomás, Luis and Agustín.

There is a rather strange gap in Bachiller's activities between 1928

and 1933. He had been a very active contributor to the Spanish

Mathematical Society and to its journal as we described above.

However this all stopped during these five years when he also seemed

to vanish from the Mathematical Laboratory. It is likely that this

was due to a disagreement with Rey Pastor. As Glick writes in [2]:-

His relationship with Rey Pastor was ambivalent. They considered

themselves good friends but constantly quarrelled. On one occasion,

when Rey Pastor criticized Blas Cabrera, Bachiller defended the

latter, saying that while the physicist had accepted a scholarship

in Strasbourg, largely at his own expense, Rey Pastor had gone to

Argentina "for three pesetas."

It is likely that some criticism of Bachiller's writings by Rey

Pastor and the pointing out of two errors in an article on algebraic

curves published by the Spanish Academy of Sciences caused him to

give up much of his activities. The Spanish Mathematical Society

reported (see [1]):-

Rodríguez Bachiller presented a proof of Poincaré's last theorem.

Rey Pastor then observed that the first part coincides exactly with

the one set out by him in 1919 in the public session held in honour

of Jacques Hadamard, and as regards the modification introduced by

Bachiller in the second part, it seems to him that it proves

nothing, for it confuses the various concepts of curve of Jordan,

Cantor and Menger. It was proposed to Rodríguez Bachiller that in

the next session he present in writing the proof, corrected, so it

can be examined again, and the author has promised to do this.

However, Bachiller did not present a further version of his paper

and neither he nor Rey Pastor were present at the following meetings

of the Society. In fact in the 1931 list of members of the Spanish

Mathematical Society Bachiller's name does not appear. Of course,

Bachiller had never submitted a thesis for a doctorate so he may

well have decided that he needed to concentrate on his research

rather than do work for the Spanish Mathematical Society.

In October 1932 Bachiller's became an acting professor when the

chair of differential equations became vacant. In July 1934 a

competition for the Theory of Functions chair was announced. Two

candidates applied, Bachiller and R San Juan, and a committee was

set up to carry out the competition. The committee summoned the two

candidates to appear before them on 15 June 1935 but only Bachiller

was present. He was told that he would take the tests set out by the

committee on 25 June. After he completed the tests successfully, the

committee unanimously appointed him professor on 29 June 1935.

However, since he still did not have a doctorate, he was told that

he had to submit a thesis and be successfully examined before taking

up the chair. He submitted his thesis Axiomática de la dimensión Ⓣ

and defended it on 27 August 1935. He passed with the grade

"outstanding" and took up the chair two days later. The thesis was

never published. He had, however, published Sobre el numero de

dimensiones de un conjunto Ⓣ in 1927 which discussed the definitions

of dimension given by Brouwer, Menger and Urysohn.

The Spanish Civil War took place from 1936 to 1939. It was a very

difficult time for everyone and Bachiller, who almost certainly

sympathised with the Republicans, tried to stay out of the conflict.

Glick writes [2]:-

Rodríguez Bachiller did not take an active part in politics, but

ideologically he was a democrat at heart. He pointed out the fright

he got when he was in Berlin in 1936; he went to greet the rector of

the University, the mathematician Ludwig Bieberbach, and the latter

replied with the Nazi salute.

He again became active in the Journal of the Spanish Mathematical

Society but much reorganisation took place as some colleagues left

Madrid. At the end of the Civil War he was treated with suspicion by

the Franco regime and "disqualified from holding positions of

leadership and confidence." He was, however, allowed to return to

his chair in December 1939. He applied for a grant to allow him to

spend four months in Rome undertaking research but his application

was refused. Nevertheless, he was able to go to Rome but he had to

make the trip at his own expense. He published Comentarios sobre

algebra y topologia Ⓣ in 1941. André Weil writes in a review:-

A short survey of some fundamental concepts in topology, leading up

to the following result: the nn th homotopy group of a topological

product is the direct product of the nn th homotopy groups of the

factors.

In 1942 he published a paper in Italian, namely Sulle superficie del

quarto ordine contenenti una conica Ⓣ. This article investigates the

existence of birational transformations based on Severi's methods.

However, after this he published no further research papers. He kept

his interest in topology, and taught courses on it many times. As a

result of Bachiller's visit to Rome, Severi and Fantappié were

invited to give lectures in Madrid and Barcelona in the year 1942.

Bachiller had quite a wide range of different teaching duties in a

number of different institutions. He ran, in collaboration with two

others, a preparatory academy for civil engineers. During 1943-44

and 1944-45 he gave a new course, this time on topological groups,

at the Institute of Mathematics "Jorge Juan" in Madrid. In April

1946, Bachiller delivered the inaugural lecture of the Mathematics

Section of the Congress of the Spanish Association for the

Advancement of Science held in San Sebastián. His lecture, Estado

actual de la teoría de la dimensión en los espacios topológicos Ⓣ,

was not published. In 1946 the Cultural Relations Board of the

Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced that they were offering

scholarships for research and study abroad. Some were aimed at

graduates, others at professors. Bachiller won one of the

scholarships for professors and on 4 February 1947 he arrived in the

United States to begin a five month visit. The first three months

were spent at the University of Illinois at Urbana where he worked

with Oscar Zariski and then he went to Princeton where he worked

with Solomon Lefschetz, Emil Artin and Claude Chevalley. Despite

working on interesting research projects, he refused to publish his

results. He also refused to publish the lecture notes of the courses

that he gave.

He delivered topology courses at the Institute of Mathematics "Jorge

Juan" up to 1951 when to changed to giving courses on logic and the

foundations of mathematics, topics that had always interested him.

In early 1955 he went to the Institute for Advanced Study at

Princeton, where he visited Einstein a few days before his death. In

the summer of 1956 he attended a topology congress in Mexico. During

this time Bachiller continued his work as a translator, and made

visits to Puerto Rico whenever he could. His final major work as a

translator was with the three volumes of Severi's Lecciones de

análisis Ⓣ (1951, 1956, 1958). Meanwhile, his first stay at the

University of Puerto Rico in Mayagüez was in 1954, and he returned

several times over the next years to deliver courses on topology and

abstract algebra. Puerto Rico, of course, was special to the

Bachiller family since Jeaús Bachiller had been born there and his

mother, who had died in childbirth, was buried there. In fact

Bachiller spent so much time in Puerto Rico that he had to resign

from many of his roles in Madrid. He even had problems in 1965

because he was in Puerto Rico when he should have been lecturing in

Madrid. However, he managed to continue to keep both his positions

in Puerto Rico and in Madrid until he retired in 1969.

In Puerto Rico he enjoyed the same enthusiasm that he had

experienced in Spain before the Civil War. He was a member of the

Philosophy Society there and was described in these terms by a

member (see [1]):-

There was Rodríguez Bachiller, a mathematician with a humanist bias,

with an intellectual curiosity open to all horizons of culture.

There were abundant examples of philosophical and literary works,

classical and modern, many of them in their original language, in

the very large library of his house in El Viso, and he could read

works in French, English, Italian and German, and did so habitually.

Another of his great hobbies was music. ...